The Japanese once had a reputation for being hardworking. I wonder if that is still

true to this day.

Most of the books selected for this list were written from the 1990s through the 2010s, during the Heisei era that started in 1989 when the current Emperor Akihito succeeded to the throne. The unprecedented boom of the bubble economy was soon followed by repeated economic slowdowns. Even so, such daily necessities as food, clothing, and shelter remain abundant, and there are very few characters in these books who work themselves into the ground.

Heisei has been an era of many changes. The drive toward rising in life that was an inextricable part of modernization since the Meiji era (1868–1912) is a thing of the past, and more young people—in the real world as well as in fiction— are living separately from company organizations. There is no guarantee that elites with superior academic records will enjoy high earning power. In the 2000s men started actively sharing the housework, raising children, and preparing packed lunches for their families. At the same time, there has been no end to the graying of the population. The works in this collection feature young single mothers, vexed by the difficulties of looking after children; households consisting of a divorced father and children; middle-aged women hoping for the death of parents with long-term illnesses; and retired people who do not have enough money to get by. They richly detail such shadows of contemporary society.

There are no longer any fixed family structures or standard lifestyles in Japan. Blood and community ties have weakened to the point where people began talking about a “society without bonds,” a period followed soon afterward by the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, and the ensuing Fukushima nuclear accident. The unprecedented shock sent the Japanese people in a new direction. A recent work from an author who lives in the affected area in Tōhoku is presented here as an example.

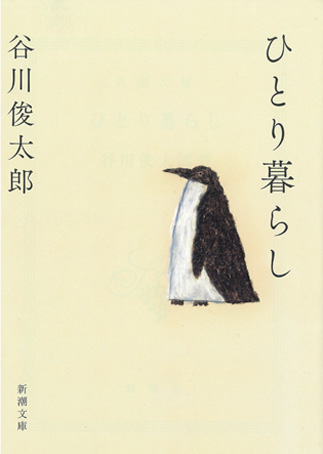

Even so, it bears repeating that this country has enjoyed 70 years of peace since the end of World War II; most people live comfortably without being troubled by life-and-death concerns in their everyday routine. The venerable poet Tanikawa Shuntarō describes this leeway as “a space or gap in which to touch others’ hearts.” Perhaps the writers of this period are the kind to peer intently through these everyday gaps to perceive the squirming somethings that lie deep below the surface of the familiar, seeking to imagine the stealthily approaching crises to come.

Since ancient times, the Japanese people have lived while contemplating the beauty of nature found in the sky and the land. This peaceful observation, unconnected to diligence at work, appears to have provided a nurturing environment for the country’s literature and poetic sentiment.

Ozaki Mariko, Editor, Culture News Department, Yomiuri Shimbun

December 2015