This book contains five mysterious, slightly scary short stories in which everyday space and time seem to twist out of joint. In the first story, “Yume de aimashō” [Let’s Meet in Our Dreams], a dreaming boy meets another boy inside his dream, but the two then lose track of which is which. In “Doko ni mo yukenai michi” [The Road to Nowhere], a boy who tries to take a different route home from school than usual finds the way much longer than he expected. He finally arrives at what he believes his home, but he catches only a glimpse of his parents, their faces contorted with fear at his transformation into a boneless, jellyfish-like thing. In “Boku wa gokai de” [I’m on the Fifth Floor], a boy finds that he is unable to leave his home in a public housing complex. His terror at being lost in a maze feels very real.

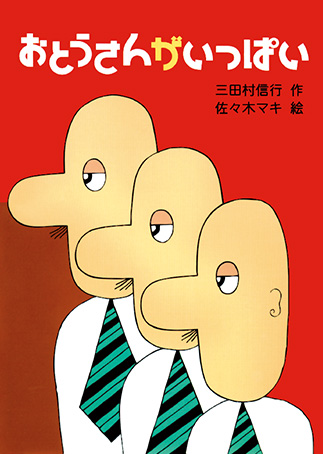

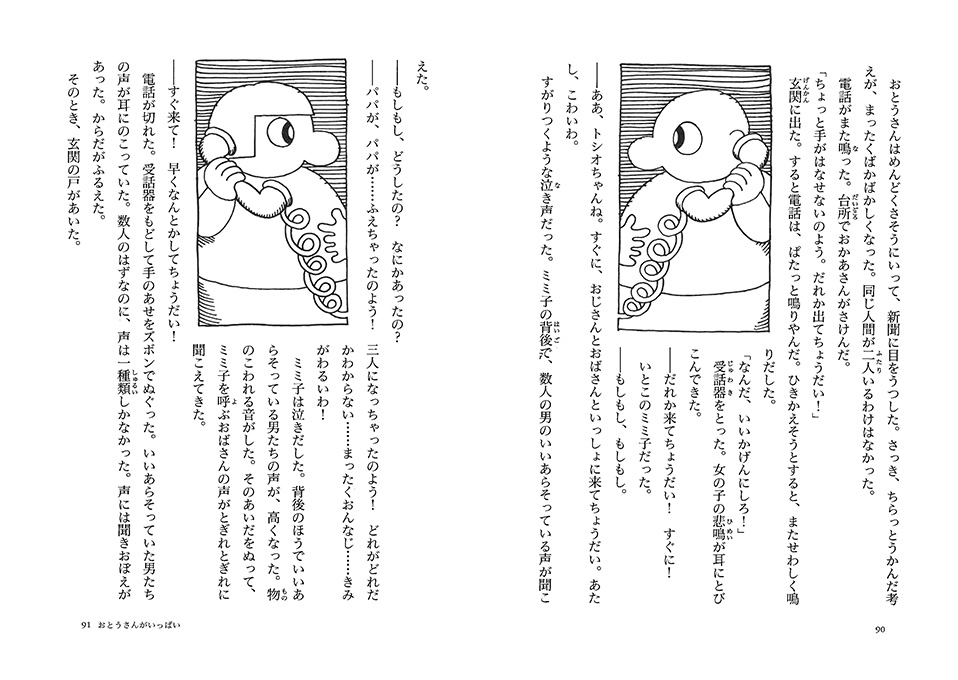

The title story, “Otōsan ga ippai” [Too Many Dads], begins with a telephone call from the protagonist’s father . . . even though his father is at home with him already. A third father then appears, and each insists that he is the boy’s real father. In the end, the government forces the child to choose one, gives the chosen father a document to certify his status, and takes the other two away into state custody—an oddly terrifying denouement. Meanwhile, in “Kabe wa shitte ita” [The Wall Knew], the protagonist’s father disappears into a wall.

Each of the stories takes some truth that everyone unquestioningly takes for granted and warps it bizarrely. The mysterious atmosphere that results subtly urges the reader to ponder deeper questions—What is family? What is the parent-child relationship? And what does it mean to be alive in this world? (NA)

The title story, “Otōsan ga ippai” [Too Many Dads], begins with a telephone call from the protagonist’s father . . . even though his father is at home with him already. A third father then appears, and each insists that he is the boy’s real father. In the end, the government forces the child to choose one, gives the chosen father a document to certify his status, and takes the other two away into state custody—an oddly terrifying denouement. Meanwhile, in “Kabe wa shitte ita” [The Wall Knew], the protagonist’s father disappears into a wall.

Each of the stories takes some truth that everyone unquestioningly takes for granted and warps it bizarrely. The mysterious atmosphere that results subtly urges the reader to ponder deeper questions—What is family? What is the parent-child relationship? And what does it mean to be alive in this world? (NA)