The Tōno region, nestled amid the mountains of Iwate Prefecture in northern Japan, is famous for its folktales. Its residents have long resided among mountains, rivers, and fields filled with mystery, and this resulted in a wealth of stories which are still told to this day. The original Tōno monogatari [trans. The Legends of Tōno] was published in 1910 by folklorist Yanagita Kunio, collecting stories gathered by Sasaki Kizen, a Tōno native himself.

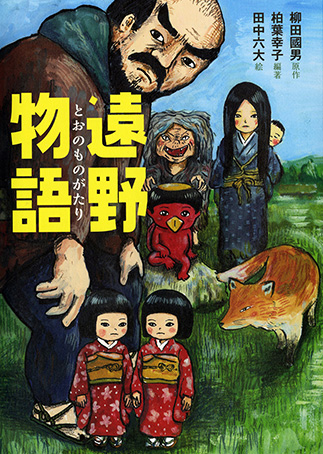

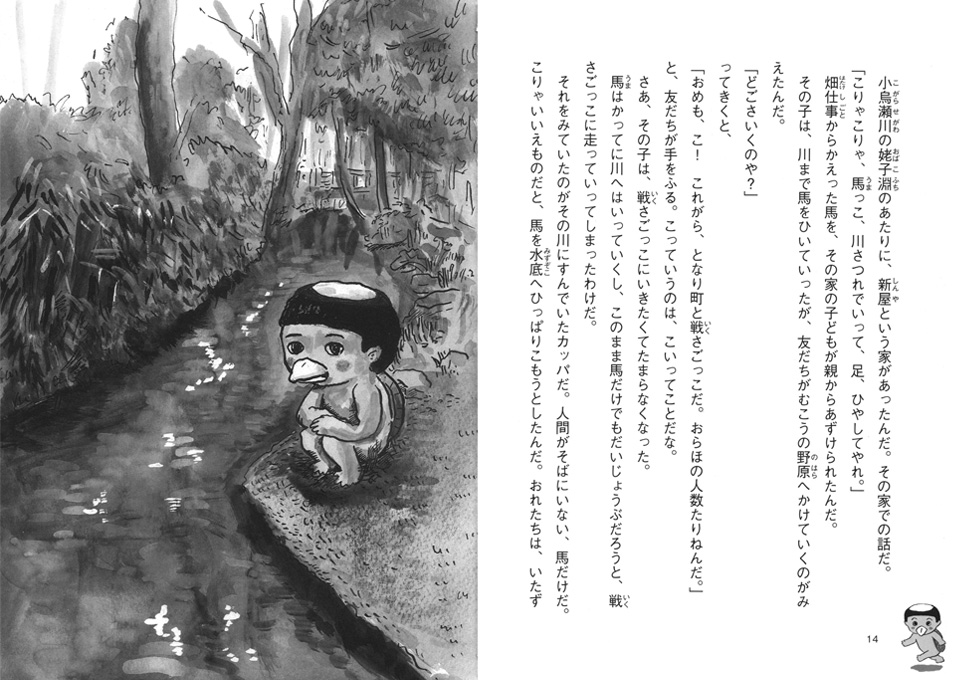

Kashiwaba Sachiko’s 2016 Tōno monogatari is a retelling of the stories from among Yanagita’s collection that the author, who spent much of her early childhood in Tōno, wanted to share with the children of today. The book contains 12 tales of mysterious beings, introduced by Zumo, a local kappa (water sprite). The kappa of Tōno have the same turtle’s shell, webbed feet, and water-filled depression in the crown of their head as kappa elsewhere in Japan, but while those kappa are green, Tōno kappa are red.

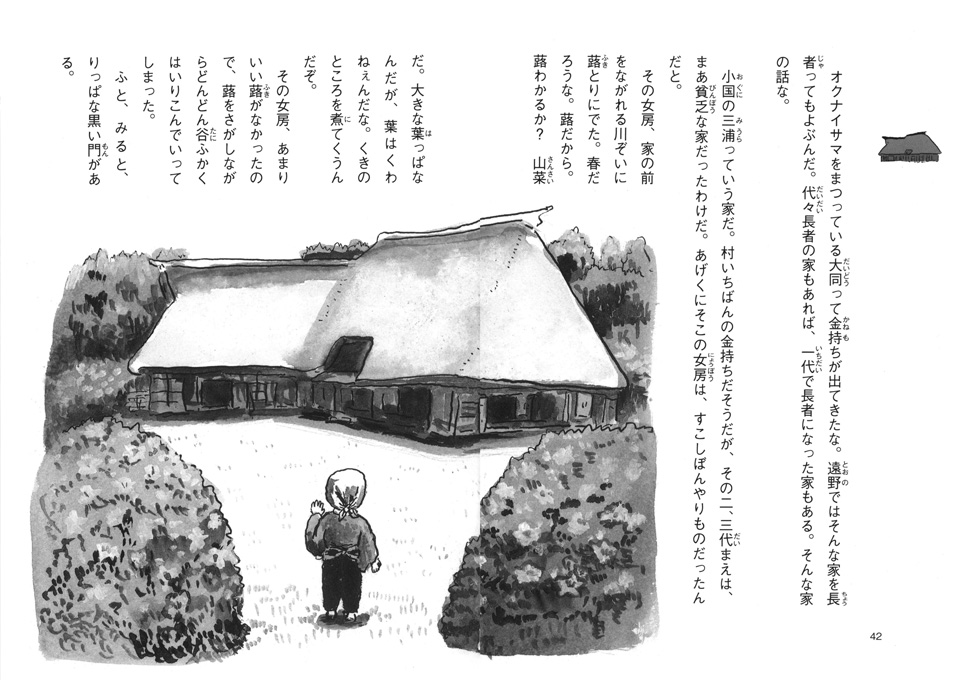

The beings that appear in the book range from charming to terrifying. The zashiki-warashi, a household deity that looks like a child; the mayoiga, a house that suddenly appears in the mountains; the futtachi, an aged beast that torments humans . . . some of the stories are sad, even cruel, but others are humorous. Each is filled with individuality. There are tales that do not end with a “Happily ever after,” and others that defy comprehension entirely; in Tōno, all have traditionally told to children and grandchildren as true stories. Even Sasaki Kizen’s great-grandmother makes an appearance. It seems she appeared before her family 27 days after her death, perhaps not feeling ready to leave the mortal plane. Even today, the people of Tōno live side-by-side with mysteries. (SJ)

Kashiwaba Sachiko’s 2016 Tōno monogatari is a retelling of the stories from among Yanagita’s collection that the author, who spent much of her early childhood in Tōno, wanted to share with the children of today. The book contains 12 tales of mysterious beings, introduced by Zumo, a local kappa (water sprite). The kappa of Tōno have the same turtle’s shell, webbed feet, and water-filled depression in the crown of their head as kappa elsewhere in Japan, but while those kappa are green, Tōno kappa are red.

The beings that appear in the book range from charming to terrifying. The zashiki-warashi, a household deity that looks like a child; the mayoiga, a house that suddenly appears in the mountains; the futtachi, an aged beast that torments humans . . . some of the stories are sad, even cruel, but others are humorous. Each is filled with individuality. There are tales that do not end with a “Happily ever after,” and others that defy comprehension entirely; in Tōno, all have traditionally told to children and grandchildren as true stories. Even Sasaki Kizen’s great-grandmother makes an appearance. It seems she appeared before her family 27 days after her death, perhaps not feeling ready to leave the mortal plane. Even today, the people of Tōno live side-by-side with mysteries. (SJ)