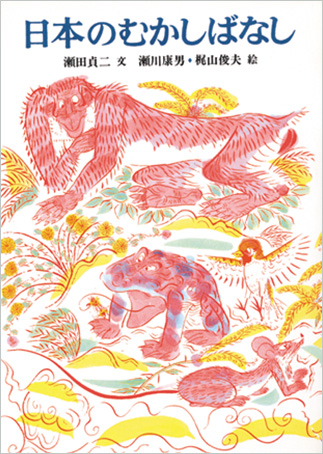

There are countless books of Japanese folktales, but this one stands out for three reasons. First is the expert eye of its author, Seta Teiji, who has translated The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, and numerous other notable foreign titles into Japanese and left an enormous legacy in the field of Japanese contemporary children’s literature. Using his far-reaching, international perspective on the world of narratives, Seta carefully hand-picks 13 stories, including some lesser-known tales in place of much celebrated classics. For example, the famous Momotarō [trans. Peach Boy] is absent from this collection, perhaps because it was appropriated for wartime propaganda purposes,.

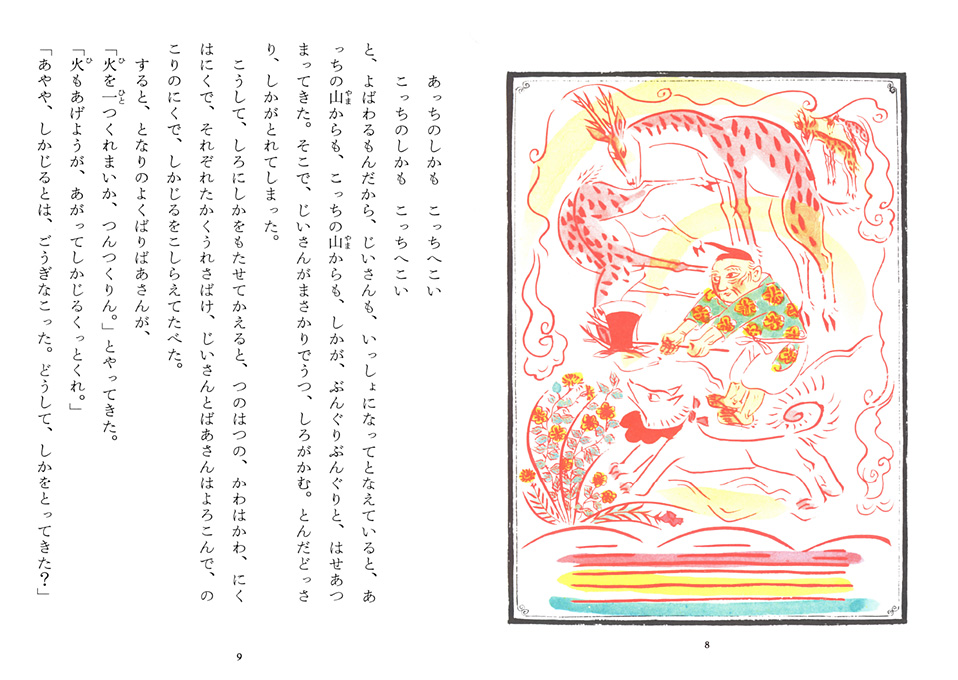

The second reason this book stands out is the fun, lively energy pervading the stories. As the author of works like Osanai ko no bungaku [Literature for Little Ones], Seta has a keen understanding of what children engage with. His chosen stories work just as well when read aloud to younger children as when read by younger school-aged children themselves. The language is simple enough for children to understand, and with a healthy heaping of funny, bouncy onomatopoeia.

Third, although Seta renders the tales in standard Japanese, he retains the rhythmical charms of the dialects they were traditionally told in, particularly in the dialogue. The essence of Japan’s regional storytelling traditions is ably distilled in this collection.

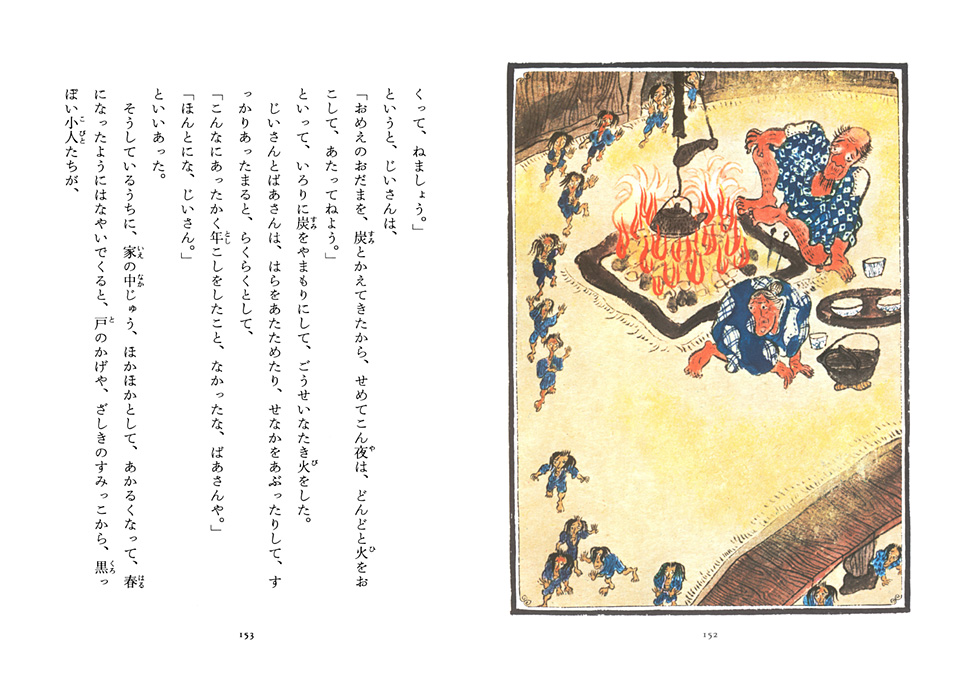

One of the highlights is “Hanasaka-jii” [trans. The Old Man Who Made Flowers Bloom], a story about a man who sprinkles ashes on dead trees to bring them into bloom. Seta’s telling paints the narrative in new shades and tones, giving a classic tale a compellingly fresh feel. From “Nezumi no sumō” [trans. The Sumo Wrestling Mice] and “Saru no mukoiri” [The Monkey Son-in-Law] to “Mameko jizō” [The Bean and the Bodhisattva], “Suzume no katakiuchi” [trans. The Sparrow’s Revenge], and “Sanmai no ofuda” [The Three Charms], the 13 mysterious tales in this collection convey the unique humor and pathos of Japanese folktales with an enchanting touch. (NA)

The second reason this book stands out is the fun, lively energy pervading the stories. As the author of works like Osanai ko no bungaku [Literature for Little Ones], Seta has a keen understanding of what children engage with. His chosen stories work just as well when read aloud to younger children as when read by younger school-aged children themselves. The language is simple enough for children to understand, and with a healthy heaping of funny, bouncy onomatopoeia.

Third, although Seta renders the tales in standard Japanese, he retains the rhythmical charms of the dialects they were traditionally told in, particularly in the dialogue. The essence of Japan’s regional storytelling traditions is ably distilled in this collection.

One of the highlights is “Hanasaka-jii” [trans. The Old Man Who Made Flowers Bloom], a story about a man who sprinkles ashes on dead trees to bring them into bloom. Seta’s telling paints the narrative in new shades and tones, giving a classic tale a compellingly fresh feel. From “Nezumi no sumō” [trans. The Sumo Wrestling Mice] and “Saru no mukoiri” [The Monkey Son-in-Law] to “Mameko jizō” [The Bean and the Bodhisattva], “Suzume no katakiuchi” [trans. The Sparrow’s Revenge], and “Sanmai no ofuda” [The Three Charms], the 13 mysterious tales in this collection convey the unique humor and pathos of Japanese folktales with an enchanting touch. (NA)